A Word About Culture: Part Four

This is the fourth post in a series inspired by a Harvard Business Review article, “The Hard Truth About Innovative Cultures”, that posited these five characteristics of effective corporate cultures:

- Tolerance for Failure but No Tolerance for Incompetence

- Willingness to Experiment but Highly Disciplined

- Psychologically Safe but Brutally Candid

- Collaboration but with Individual Accountability

- Flat but Strong Leadership.

In our last episode, we pondered the role of respect in psychologically safe but brutally candid environments. In this episode, we contemplate the importance of coupling collaboration with accountability.

Free To Do It Well

The article from which this series derives has this to say, in part, about combining collaboration with individual accountability:

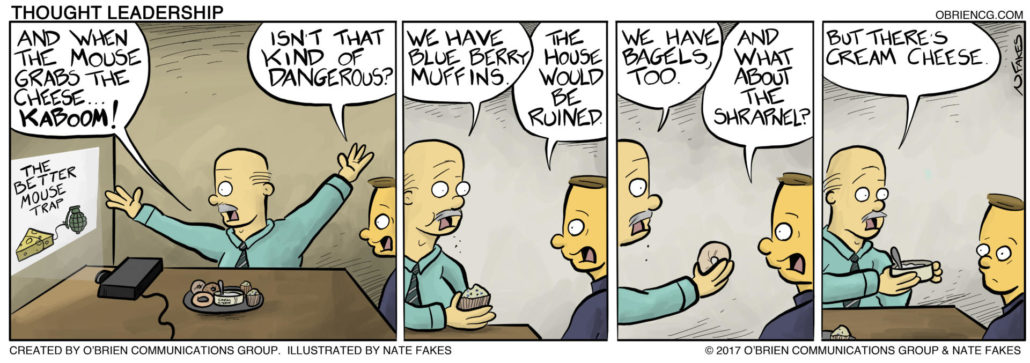

People who work in a collaborative culture … have a sense of collective responsibility. But too often, collaboration gets confused with consensus. And consensus is poison for rapid decision making and navigating the complex problems associated with transformational innovation. Ultimately, someone has to make a decision and be accountable for it.

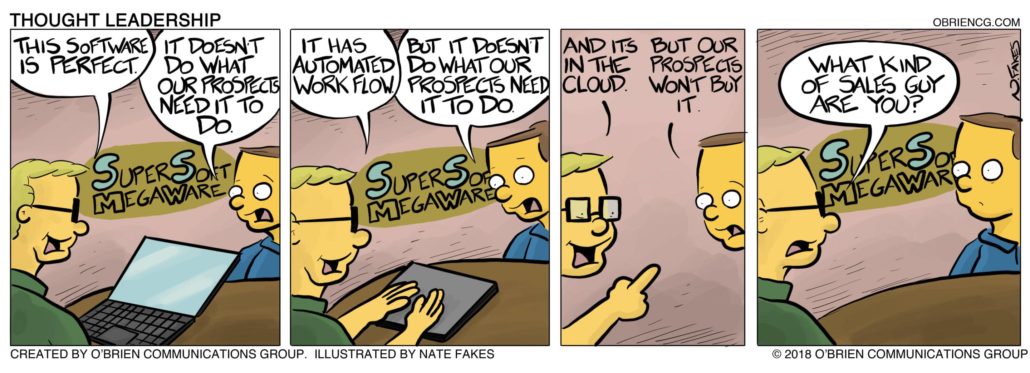

While the people in our organization do, indeed, possess that collective sense of responsibility, we facilitate the success of their efforts — collaborative and individual — by ensuring our people are given responsibility and authority. Making people responsible for things — without giving them the authority to make appropriate decisions about them — sets those people up for failure.

Giving a competent person responsibility for achieving something — but giving decision-making authority to another person (who may be less competent, less responsive, less knowledgeable about the responsibility, or simply more detached from it), puts both of them in ineffective, inefficient positions. That’s why we make sure our people are free to do their jobs well.

If We Don’t Succeed, Our Customers Can’t Succeed

The other reason, of course, for assigning people authority for their responsibilities is that, as an organization, we want to be as responsive to our customers as possible. We do believe that two heads are better than one (collaboration). But we also believe good decisions made promptly are preferable to perfect decisions (which aren’t possible) made later. That’s why we strive to maintain an environment in which our customers succeed because we succeed.

Our customers and our employees seem to think that works pretty well.