The Tell in Artificial Intelligence

tell (noun)

- In poker, a tell is a change in a player’s behavior or demeanor that allegedly reveals information about his hand strength. This can include facial expressions, nervous habits, or mannerisms that are believed to be indicative of a player’s assessment of his hand. A tell can be used to gain an advantage by observing and understanding the behavior of other players, but it can also be faked or misinterpreted.

- A tell can also refer to any behavior or action that reveals a person’s true intentions, emotions, or thoughts, often unintentionally. This concept can be applied to various aspects of human interaction.

In February of this year, we published a post called, “The Art in Artificial Intelligence”, in response to an article we read in the December edition of Best’s Review. We stand by the balance of optimism and skepticism we struck in that post. And we found that balance validated in the October edition of Best’s Review. That edition ran an article called, “Artificial Intelligence’s Imperfections Become Clearer.” Is it a condemnation of AI? Not by a long shot. But in identifying some of AI’s tells, it does sound cautionary notes worth heeding.

Exhibit A

First, the article offers this slice of sensibility:

How can insurance underwriters, using AI, separate fact from fiction? Could AI be wrong? AI systems can be imperfect and may produce erroneous outcomes if they are trained on biased or inadequate datasets. Add to those false pathways, poor data integration, algorithmic bias and decision-making errors and, yes, AI can be wrong. Examples may include denial of a claim due to not having the correct nomenclature programmed into and recognized by AI. At times, AI will confidently, yet inadvertently, omit information, such as a street address; or list a medical condition that a claimant may not have had; or fail to post electronic fund transfers in a timely manner for premium payments, resulting in a notice of cancellation.

It’s fair to imagine the differences between fact and fiction are seldom considered when it comes to AI. But the fact is AI still requires programming and accurate data. So, it’s still subject to GIGO.

Exhibit B

Then the article ups the ante, extending its considerations to insurance companies in their entirety:

What about “business decisions” made by insurance carriers when a loss occurs? Can AI make decisions based on business relationships and long-term client loyalty … what data points go into that algorithm? AI … offers a huge amount of promise for the insurance industry. But mitigating uncertainty … has to be at the forefront of asserting the risk decision-making for accuracy by machine and human on paper and online.

Insurance companies may be built on products and services. But they’re sustained by minimizing losses, maximizing and maintaining business relationships, and ensuring the loyalty of policyholders. Those things are not worth risking to AI or anything else.

Our View

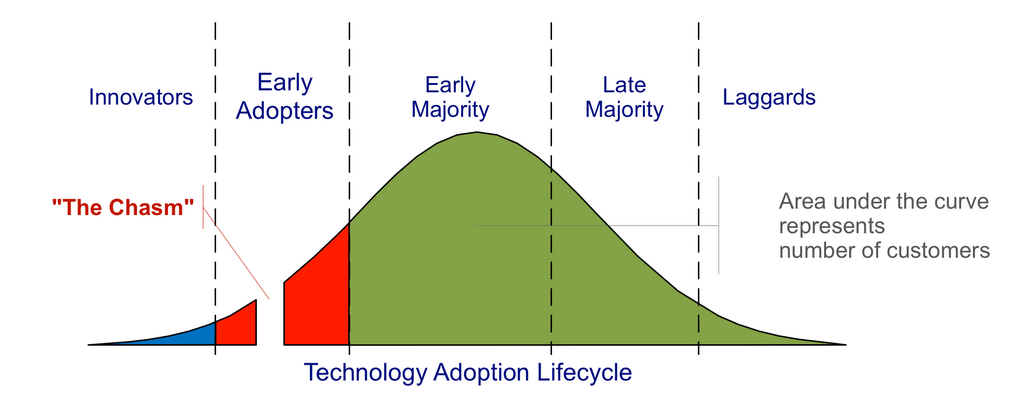

We tend to think of AI in terms of the classic technology adoption lifecycle, which mimics the bell curve. We don’t need to innovate with it. We don’t need to be early adopters of it. But we do need to keep our eye on it, to learn about it, and to employ it in ways that will best — and most reliably — serve our customers. Then, especially if it turns about be anything like the dot-com bubble, neither we nor our customers will pay any undue prices should the bubble burst.

Image by Craig Chelius, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

We’re not in the business of building every bell and whistle we can think of. And we’re not inclined to weigh our product down with unnecessary functionality. We are, however, very much in the business of giving our customer what they need when — and because — they need it.

As the saying goes, reliability is in the AI of the beholder.

Brilliant piece! I love insurance